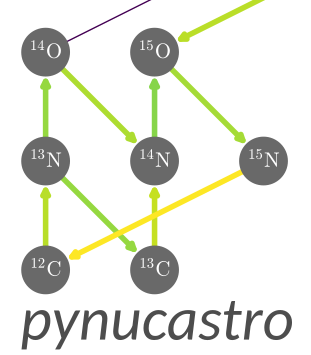

Derived Rates#

In this section we discuss the implementation of

DerivedRate

via detailed balance.

We will also discuss the partition functions mentioned in

Rauscher and Thielemann [2000] and Rauscher [2003]

with the purpose to compute inverse rates at extreme temperatures and

heavy nuclide conditions.

Semi-relativistic ideal gas model#

In order to illustrate our implementation, we will start first by computing the number density of reaction specie in terms of its chemical potential. Let us start our discussion by introducing the 1-particle canonical partition function by

Our purpose is to compute the number density in terms of the chemical potential by assuming a first order velocity approximation of the energy, internal excitation energy, rest energy and coulomb screening potential for each particle as:

From this point, we may compute the N-particle canonical partition function by

and by using the fugacity parameter, defined by \(z=e^{\mu/(kT)}\), we also may compute the grand-canonical partition function:

with the associated grand-canonical potential:

and the number of particles may be computed as the first derivative of the grand-canonical potential with respect to the chemical potential \(\mu\):

From the number density definition, \(n=N/V\) we may compute finally, the relationship between the number density and the chemical potential for a semi-relativistic ideal gas by:

or equivalently,

as summarized in [Rauscher and Thielemann, 2000].

Often times we want to work in massfractions, \(X_i = m_i n_i / \rho\), or in molar fractions, \(Y_i = X_i / A_i\). Hence:

Partition functions#

Until now, we have not discussed the role of \(g\), which encompasses the number of spin states that a particle may adopt. Now, since the ingoing and outgoing particles are far apart in comparison with the nucleus size before the collision takes place; this allow us to assume that particles are likely in their ground state as they approach. Hence to account for state degeneracy, \(g = 2J_0 + 1\), where \(J_0\) is the particle spin in the ground state. However, particles may be in a superposition of states due to excitation of upper levels, with excitation energies \(\Delta_l\), caused by an steady increase of the temperature. As pointed out in [Rauscher and Thielemann, 2000], we have to replace \(g \rightarrow (2J_0 + 1) G\), where \(G\) is the internal partition function normalized by the ground state spin.

Note

ReacLib rates with -v flag are derived similarly, but setting \(G = 1\).

Implementing partition functions#

The partition function information is contained in three main classes:

PartitionFunctionmaterialize the temperature and the partition function values into an object, interpolating across all the defined points using a cubic spline interpolation. If a temperature value is outside the temperature range, we keep its value constant to the nearest boundary value.PartitionFunctionTablereads a table and construct a dictionary between each nucleus and their partition function class object.PartitionFunctionCollectioncollects all the formatted table information, inside/nucdata/PartitionFunction/. It allow us to include the high temperature tables in [Rauscher, 2003] and to select the model used to compute the partition functions, respectively. By default, we include high temperatures, and our partition function model to be the finite range droplet model (FRDM). If a nucleus is not in the collection, we set the partition function values to 1.0 by default.

Inside the Nucleus class,

we have defined set_partition_function() which setup our partition function

collection, our high temperatures consideration, and the model used to compute

the partition function data. On the other hand, get_partition_function()

assigns a partition function class object to the defined nucleus.

Let us illustrate how it work:

import pynucastro

co46 = pynucastro.rates.Nucleus('co46')

pCollection = pynucastro.nucdata.PartitionFunctionCollection()

co46.set_partition_function(pCollection=pCollection, set_data='etfsiq', use_high_temperatures=True)

pf_co46 = co46.get_partition_function()

Now, from this point we define a method inside a Rate

named set_partition_function() which reads a partition function collection

and setup all the nucleus inside the reaction rate. Let us illustrate now,

how it works:

import pynucastro

p_collection = pynucastro.nucdata.PartitionFunctionCollection()

o18_pg_f19 = pynucastro.rates.Rate('../library/o18-pg-f19-il10')

o18_pg_f19.set_partition_function(p_collection=p_collection, set_data='frdm', use_high_temperatures=True)

p = o18_pg_f19.reactants[0]

o18 = o18_pg_f19.reactants[1]

f19 = o18_pg_f19.products[0]

pf_p = p.get_partition_function()

pf_o18 = o18.get_partition_function()

pf_f19 = f19.get_partition_function()

Derived rate definition#

The forward and reverse reactions are entangled due to thermodynamical and nuclear equilibrium aspects. In this section we will see how this connection is introduced and explore its consequences in the nuclear rates computation, as discussed in [Rauscher and Thielemann, 2000]. The general case is worked out in the appendix of [Smith et al., 2023]. Here we demonstrate a less general reaction channel, \(A + B \rightarrow C + D\), discussed in [Cyburt et al., 2010], for simplicity.

Starting with a pair of reaction channels, where \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), \(D\) are distinct nuclear species:

The coupled ordinary differential equations characterizing the evolution of the species can be written as the following:

where \(\nu_r = N_A + N_B - 1\) and \(\nu_p = N_C + N_D - 1\) Now, taking in consideration that forward and reverse rates are in equilibrium:

Hence the ratio between the screend forward and the screened reverse rate can be written as:

To continue further, the molar fraction at equilibrium state is characterized by the form of molar fraction that we obtained in Semi-relativistic ideal gas model with the chemical potential representing the equilibrium state, i.e. \(\mu = \mu^{\mathrm{eq}}\). With the definition of the Q-value of the reverse rate:

And the detailed balance condition, i.e. chemical equilibrium:

We finally obtain:

where \(R\) is the equilibrium ratio without the screening term and the prefactor \(K\) is defined as:

Now assuming that the electron screening routine follows linear mixing rule [Dewitt et al., 1973], then the screening enhancement factors for the forward and reverse reaction channels that we’re considering where \(\lambda^\mathrm{scn}_\mathrm{rev} = \lambda^\mathrm{uns}_\mathrm{rev} \ F^\mathrm{scn}_\mathrm{rev}\) and \(\lambda^\mathrm{scn}_\mathrm{for} = \lambda^\mathrm{uns}_\mathrm{for} \ F^\mathrm{scn}_\mathrm{for}\) will be:

Note

The only screening routine that follows the linear mixing rule is

potekhin_1998.

This is important if you want to be self-consistent with NSE.

where \(Z\) is the atomic number of the reactants involved in the reaction. With the above rule, the ratio between the screened reverse rate and the unscreened forward rate is:

Now due to conservation of charge for strong reactions:

We finally obtain:

We note the above expression is self-consistent with the definition of the electron screening enhancement where:

Therefore, the unscreened

DerivedRate

is evaluated by taking the provided source rate and multiplying it by the

temperature-dependent equilibrium ratio, \(R\). The appropriate

screening enhancement factor can then be computed and applied in the usual way,

just as for any other rate.

Note

It is completely general to compute the derived forward rate

based on the reverse rate. Examples of this are forward rates,

i.e. Q > 0, provided by ReacLib but with the -v flag.